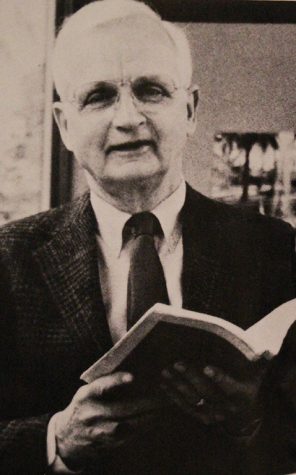

Bob Edelen Will be Missed

Imbued His Students with a Love of Literature, a Love of Learning

March 22, 2018

The autumn I was 16 brought me in touch with a book that soon had me ensorcelled. It was William Peter Blatty’s 1971 horror novel, “The Exorcist,” and it had me by the short hairs. A hint of sex, of sacrilege and supernatural awe. As a fairly chaste Catholic boy still afraid of my own submerged sexuality, I hadn’t encountered more than a smidgen of those things. Naturally, I was hooked.

But what had really grabbed my attention after I discovered the book amid the pile of paperbacks available for reading in the back of Bob Edelen’s third-floor classroom were the heavier issues beneath all the horror and hooplah. Here in Father Karris, the book’s protagonist, was a Harvard-trained psychiatrist and Jesuit priest who was just realizing he had lost his own faith just as fate was putting him face-to-face with proof of the physical reality of the Devil, and of Evil.

I had tried to get my dad to read it. It’s about God, I told him! But he rejected out of hand the notion that a horror flick made famous for its scene involving contact between a possessed little girl and a crucifix could in fact be worth his time. He was a realist.

I was not. And neither, it turned out, was my new English teacher.

Bob Edelen was in his early 60s, and boiled over with enthusiasm for so many things, it was hard not to leave his class with your head swirling. I can’t recall if I convinced him to read “The Exorcist,” though I am certain I tried. Maybe he did, and like “The Lord of the Rings,” which he eventually dipped into just to see why I was so enthralled, saw less in it than I did.

It didn’t matter. What counted was he took my interests seriously, and encouraged me to take books – all books – seriously.

I had already begun to think maybe I wanted to be a writer, though I had never met one. I had been scribbling away in my room for a few years, but to little effect. What I found out about my new teacher was that he was in love with writing. And it was intoxicating.

“Friend,” he would say to me, and to many others, in class on any given day, “When you get to college your professors will only care about one thing: ‘What have you read? Which books? Which writers?’”

That was definitely what I wanted to hear. There were plenty of things I was counting on them not to be interested in, such as my grades in physics or Spanish. In fact, a certain diminutive nun who taught honors chemistry once told me she looked at me and wept over my wasted potential. True story.

But in other classes, in English, in Eugene Eckert’s fabulous history courses, and later, when I found nourishment in Tony Lococo’s outstanding journalism classes and as part of the ECHO staff, it was a different story. Trinity put me in touch with the forces within myself longing to break out of ordinary expectations.

But none of this happened with as much force, with as much soul-lifting power, as in the two full years I spent in the Independent Studies Program with Bob.

My mind rolls back over the decades to remember those times, and to look anew at the teenager I was. I marvel at the mix of ingredients that had been assembled by Trinity, from the coaches that worked with me to the teachers that inspired me to the students who befriended me, and by the parents who sacrificed so much to pay my tuition.

There in that school, in that classroom especially, I had friends who were also moved by some of the same currents stirring beneath the sluggish waters of our half-formed brains. Rob Weber, whom I’ll probably embarrass by mentioning in this piece, was the gentlest soul I’d yet encountered. Named after Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, he was obsessed with writing, too, though his tastes and capacities were different, perhaps deeper, than mine. (They still are, as his wife and kids could tell you.)

As a young person, Rob fell under the spell of the mystical monk Thomas Merton, a favorite of mine many years later, while I was soldiering through Dostoevsky, Robert Penn Warren, Steinbeck, Cervantes and, without success, the as-yet indecipherable William Faulkner.

Edelen would have us boys sit in small groups, and turn a tape recorder on and discuss whatever we had been reading. Sometimes this was material out of his beloved anthology – “Roberts on Writing about Literature” – and sometimes it was the books we had chosen for ourselves to read among the stacks in the back.

An honors class, there were plenty of students who were far less focused on the literature and more on the path the class put them onto whatever collegiate track they were bent on, but that didn’t matter. Edelen’s gift was to encourage, without directly saying so, all of us to put down some of our guards and let the magic of the literature work its effect on us.

I never did meet in college a professor who greeted me on the first day by asking, “What have you read?” as I had been so often promised. But I did meet a man in his 70s who would become one of the great mentors of my early career as a journalist. His name was Bob, too, and he led for years a workshop for groups of executives, of judges, or pregnant teenagers, of social workers – you name it – through a weekend or a day of intense reading. Great literature, he would teach, could change your lives, no matter how great or how small those lives are when you encounter the work.

Long before I knew Bob Schulman, I had been taught a similar lesson along with brothers at Trinity by Bob Edelen.

Edelen made me want to write, because he taught me it was a valuable thing to do no matter the career I settled into later. Other mentors, Tony Lococo and Schulman among them, helped me direct those energies toward journalism, which after more than 25 years, has turned into a lucrative and productive career. Boy, the things I have seen.

Few of those things have carried the punch that arrived with last month’s news that Bob’s wife Suzie had died. She had been ill for many years, and I had last visited her a few months ago at the Providence nursing home where they had moved about a year ago. She was blind, and frail, but chipper. And still completely in love with Bob, lying in his bed across the suite.

Bob himself had been suffering from Parkinson’s for years, and it had become hard to understand his language. But he was still full of things to share, and wanted to know what I had been reading, what I had been writing. Whether I was happy. How my father was. How my friends that he remembered from high school were.

Next came news that he had died, too. Precisely a month after Suzie. I wasn’t surprised. Ever since the day he met Suzie as a grieving widow in the parish where he was the pastor, they had grown closer and closer.

He was one of the priests who left the priesthood after seeking permission from the Pope. He had been granted the permission, on the condition that he no longer perform any priestly duties in public. He told me over the years, long after I had graduated, that he never stopped thinking of himself as a priest, and he would say Mass just for himself and Suzie from time to time.

He never did lose his faith, the best I could tell. In his later years, before he was seriously ill, he had turned back to great spiritual writers and had begun laboring over the biographies of great popes. He was convinced that God is love, and that all the other works of the Church were mere trappings designed to help men and women know that love.

By the time Pope Francis came along, he had a disciple in New Albany who had been preaching his message for many years.

Love. It was so evident in later years as I got to know him as an adult. Suzie had been a widow who had turned to her priest for comfort. Over time, their feelings grew deeper and they eventually married. Bob told me long after that what had haunted him most as a priest – and he loved being a priest – was loneliness. When he met Suzie, he realized just how lonely he had been.

He and Suzie lived in a house over in Floyd Knobs, where big dogs roamed and where Bob would invite comers of all ages and abilities to come test their tennis skills. Most left with a respect for the English and power he brought to bear. I know I never won a set against him.

Later on, they moved into a little two-bedroom condo over in New Albany, above the fast-moving Silver Creek, and shared that home with a succession of little white dogs. Step into that house any time over the years and the love for each other, for that dog, and for their visitors too was so pronounced it could take your breath away.

As they grew older and older, they would sit in their chairs next to each other and hold hands while watching TV. It’s how all people should age, if they were so lucky.

It’s a mystery, how the impact of a teacher burrows so deeply into some of his or her students. Henry Adams once wrote that the power of a great teacher is impossible to measure, because the impacts one student feels are spread to others he or she meets, and then those affected impact someone else down the line. All through history.

Adams also wrote from his own time as a professor that only one student in 10 took polish.

One of the saving graces of my life was that I was the one in 10 for Bob Edelen. I know Bob affected me powerfully. I suspect his influence has been behind my commitment to writing and to ideas and to books over my life, and when I’m still and reflective, I can see how that in turn has had impact on others, on siblings, friends, nieces, nephews, and younger writers, in my life.

Bob was so full of knowledge and enthusiasm. He had studied film in New York and religion in Washington, D.C. He knew tennis and books and movies and music. His command of opera was intense. I still have on my Spotify play list the single piece of classical music that penetrated my rock-and-roll-obsessed brain as a teenager … Mozart’s “Eine Kleine Nachtmusik,” a gift by way of cassette my senior year.

From Bob, of course.

Michael Lindenberger is an award-winning newspaper and magazine writer who got his start as a writer and editorial page editor at the ECHO while a student at Trinity High School. He’s a former state correspondent for The Courier-Journal, a graduate of U of L’s law school, and a 2013 John S. Knight Journalism Fellow at Stanford University. He currently serves as a member of the editorial Board at The Dallas Morning News, where he is editorial writer, columnist and the paper’s former Washington correspondent for business.

David Rice • Apr 25, 2018 at 3:19 pm

It is sad to hear of the passing of Mr. Edelen. His Junior and Senior ISP English classes were the spark to my lifetime love of reading and literature. I still have my Roberts book, and even after the many other tomes studying English in college, it’s still the only textbook I have kept. Thank you, Mike for the wonderful remembrance of my favorite teacher ever.